What makes a whistleblower? This is the question I asked myself, sitting in the audience at the HSJ Patient Safety Congress in 2023. Peter Duffy, consultant urological surgeon, had spoken frankly about his experience. He gave advice to doctors who were considering such action. Never do it alone – Trust nobody – Keep emails and files on your own computer, as they will delete everything. It was sinister, as though NHS organisations under threat of reputational damage functioned like a police state or a corrupt government. This view has been supported by journalists Janet Eastham and Gordon Rayner in a series of Daily Telegraph articles (£), where they describe the experiences of 52 whistleblowers. Exclusion, under-mining, a ‘playbook’ of tactics.

Duffy showed an email that appeared to confirm his knowledge of a certain patient who needed urgent urological intervention. Until it was discovered, there was no evidence to suggest that Duffy was responsible for arranging an urgent intervention for the unwell patient. After five years, during which time all emails connected to the case had been retrieved and sent onto the investigators, it suddenly appeared. Duffy alleges that it was fabricated. He showed it to us on a huge screen. My God, I thought, it looks real to me – the language, the tone. Do I believe him? If not, am I siding with the organisation?

The details are too Byzantine (a feature of many such cases) to go into here, but they are described in two books written by Duffy. History appears to have made its decision. He received damages for unfair dismissal, and is lauded as a champion of patient safety. Moreover, he received a MBE from Prince William in 2022, for his services to the people of the Isle of Man during the COVID-19 pandemic. He is a good man. Is it possible that he misinterpreted certain information? Could there be more than one side to the story? Are whistleblowers always right? How do they maintain self-belief when all around them appear to doubt them?

▲

The need for people to speak up became clear after the Mid Staffs scandal. Sir Robert Francis, in his report, referred to the importance of staff, especially juniors, being ‘the eyes and the ears’ of an organisation, the ones who are close enough to the ground, who see things as they really are. The NHS recruited ‘speak up guardians’, objective, approachable, non-judgmental and unbiased staff who could take the concerns that were presented to them and seek resolution. Each year, the national guardian publishes a summary of concerns that have been raised. In 2022-2023, there were 25,382 escalations. 22% related to bullying and harassment. 30% of cases involved inappropriate behaviour or attitudes. This is unsurprising: poor relationships are at the heart of many safety issues in the NHS, Peter Duffy’s case being one example. The independent investigation, by NICHE, uses the word ‘relationships’ (often preceded by ‘poor’) 95 times in its 225 page report.

What is whistleblowing? Robert Francis defined the whistleblower as “a person who raises concerns in the public interest. For the purpose of concerns relating to the NHS, and in particular patient safety concerns, the term ‘whistleblower’ is used in this report to apply to those who speak up when they see something wrong usually relating to patient safety but also to the integrity of the system.” Sir Anthony Hopper, when asked to write a report about it in 2015, concluded, “It is sometimes said that a whistleblower is a person who raises concerns externally, that is with persons other than his or her employer. This is not right.” Therefore, if you or I send an e-mail to our manager (clinical, non-clinical) about something that we are not happy with in our department, something that represents a threat to patient safety or is morally unacceptable, we are whistleblowers. Many of us will have done this.

I will now explore different examples of whistleblowing to tease out the elements that make them unique and from which we can learn.

▲

In 2020, an anaesthetist with back pain inserted a cannula into himself and injected a non-opiate painkiller. It was noticed, and those who saw it knew it was inappropriate. The same anaesthetist was involved in a peri-operative death. An infusion was given incorrectly, although it was not directly related to the patients’ outcome. Later, the family of that patient received an anonymous letter, reproduced below.

We think you should know that the consultant anaesthetist who made the mistake with the fluid into the arterial drip in theatre should never have been at work. He had injected himself with drugs before while in charge of a patient and it was all hushed up and he was at work like nothing at all had happened – but we all knew the truth. You need to ask questions about this doctor and what investigations had been had about him before. We think there is a big cover up. Operating Theatre Staff.

The trust swung into action. It tested the letter for fingerprints, and requested that all staff who might have sent it attend to have their fingerprints taken as well. The whistleblowers were being hunted. A classic example of an aggressively defensive response. But… in Christine Outram’s independent report, it is made clear that the sending of this letter was wrong! The whistleblowers were themselves the cause of a Serious Incident. Outram concludes,

In this case we see that whisteblowers, while being morally right, must observe the rules within which they work. The question could reasonably be asked however – would anyone have done anything if the letter had been sent? By going around the usual routes, it prompted the family to contact the coroner and forced the organisation to confront an issue.

▲

Lucy Letby was found guilty of the murder of seven babies and the attempted murder of six others. In my mind, nothing worse could happen in a hospital. Yet, there were people there who had already worked out that she was the common factor, and that she was probably responsible. The paediatricians involved escalated their concerns, but the trust took time to take action. At one point, the whistleblowers were asked to enter a mediation meeting and write a letter of apology to Letby. It is clear now that had she had been removed from the clinical area sooner, fewer babies would have died. Attention has now focused on the nursing director who, it seems, was unable to accept the possibility that one of her staff was a murderer. What does this case teach us?* Perhaps, it is about suspicion or distrust between staff groups – a very sad state of affairs if true; perhaps it is the inability to think the unthinkable, and to take action ‘just in case’ an allegation true. By taking action in such cases managers bring on so many negative consequences, while remaining unsure about the truth of the allegation – they will destroy the accused’s career, they will invite police onto the wards, they will bring all kinds of negative attention. In retrospect, if a crime is proven, they will be applauded for their swift intervention; but what will become of them if it all turns out to be a false alarm? We need to consider the sense of risk in those who receive escalations. Interestingly, there is a growing concern about the safety of the conviction. An article written in The New Yorker has cast doubt out on her guilt. UK readers were blocked from reading it. Nothing is straightforward.

▲

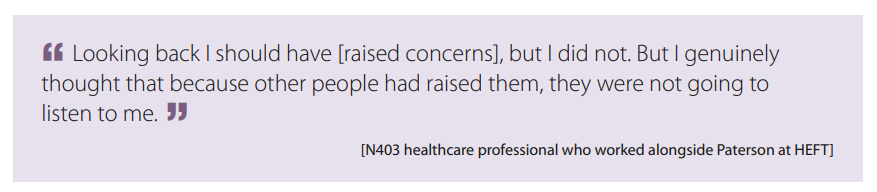

Ian Paterson is in jail. He was found guilty of performing hundreds of unnecessary breast surgeries, and to a poor standard. He worked in NHS and private hospitals, and the timeline of the concerns that accumulated around him is very prolonged. He arrived in Birmingham with a sullied reputation, having been suspended from the Good Hope hospital before he was even appointed to the Heart of England hospital. In 2003, five years after his appointment, he was investigated because of concerns about his surgical methods. He was not barred from operating until 2011 (and was eventually found guilty of wounding with intent in 2017). The machinery of investigation moves slowly, especially between when public and private sectors are involved. Sir Ian Kennedy, the same man who investigated the Bristol heart scandal many years before, was asked to undertake an inquiry. He heard from numerous individuals that their concerns were dismissed. They did not persist. Later, Bishop Graham James chaired the independent inquiry. The psychology of those who could have blown the whistle longer and louder is well described.

▲

We come back to Birmingham. University Hospitals Birmingham (UHB) trust hit the headlines when a junior doctor, Dr Vaishnavi Kumar, committed suicide after leaving a note saying that on no account, if she were to be found alive, should she be taken to her own hospital. It was here that Mr Tristan Reuser, consultant eye surgeon, was disciplined for asking a manager to assist him in an operation. This was his second offence, the first being his absence while attending a BMA meeting. However, he had previously emailed his managers raising concerns about the staffing of operating lists. He was referred to the GMC for misconduct. A Freedom of Information request found that 26 doctors had been referred from that trust, and in each case the GMC found that there was no call for further action. These referrals appeared vindictive, each one a symptom of an organisation that dealt with troublemakers by trying to get them struck off (though a later investigation by iQ4U found the majority of these referrals were appropriate, resulting in action). The interesting quirk in this case, is that the chief executive was himself referred to the GMC. When he referred Reuser to the GMC, he did not make it clear that Reuser was a whistleblower. This is important because whistleblowers are protected in law (they have made ‘protected disclosures’). They cannot be sacked for any reason connected to their escalation. The law makes sense, but again, the fact that there are two sides of the story complicates matters. When he asked a manager to assist him in an eye operation, he must have known that this was wrong, however great his exasperation. There was urgency; the patient needed their operation before their eyesight was irreversibly damaged. Who was right? Does a whistleblower become right purely because of their whistleblowing action? Should the act of whistleblowing result in a protective shroud being placed around the complainant, come what may?

▲

One of the best known whistleblowers is Dr Chris Day. He was working in an intensive care unit as a junior doctor when he complained that staffing levels were unsafe. He was solely responsible for the unit overnight, as an SHO. He has been in an endless series of tribunals and hearings, and it has cost him hundreds of thousands of pounds. His career has been ruined. Rather than give up and get on with his career, he chose to keep fighting. As is often the case when the legal profession becomes involved, the details of his battle for justice are bewilderingly complicated. I can barely it follow myself, as an interested person. The lesson I take from his campaign is that whistleblowing can change your life.

▲

Whistle blowing is not unique to medicine. Journalist Rajkumar Keswani, who died during the COVID-19 pandemic, predicted the Bhopal gas disaster. He is now regarded as a Cassandra, so-called after the Trojan Princess who tried to warn that the Greeks were coming, but who was cursed, despite for gift of prophecy, to be ignored. Keswani described himself as a lone voice in the wilderness. No one in power listened to him, and tens of thousands of people died and continue to be affected to this day. It was observed that had he succeeded in his task of achieving change in the management of the gas plant, and the catastrophe had not occurred, no one would know his name today. The whistleblower becomes famous, or notorious, in the context of the disaster that they did not prevent.

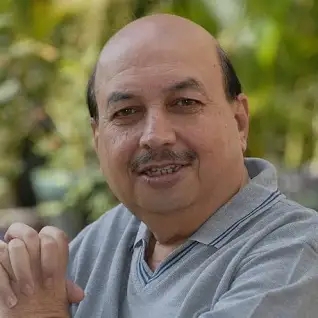

In 1986 the space shuttle Challenger exploded. The investigation (Rogers commission) concluded that the O-rings were poorly adapted to the cold weather, and were not flexible enough to seal the fuel tank on the morning of the launch. Fuel leaked out and ignited. This had been predicted. Roger Boisjoly and Allan McDonald, working for the engineering firm Morton Thiokol, refused to sign off on the launch due to their concerns. They were not listened to. Subsequently, their careers stalled. In 2003, space shuttle Colombia was destroyed on re-entry. A piece of foam had broken off the external fuel tank during launch, fatally damaging the left wing. In the days between the launch and the disintegration, Rodney Rocha was one of those he understood the potential consequences of the foam impact. He campaigned for better visualisation of the wing while the shuttle was in orbit, but his requests where declined. In a recent documentary, The Space Shuttle That Fell To Earth, he was asked “You were a grown man… why didn’t you speak up?” He replied, in a slightly agitated way, “The room was full of grown men!” The lesson is that authority matters. If you are a mid-level engineer, nurse, doctor or manager, your opinion is less valuable than someone at a senior level. When a judgement call needs to be made, the most senior voices in the room will prevail. They are senior because they are experienced; their position is a recognition of their ability to make hard decisions. Therefore, they should be allowed to make those decisions. Right?

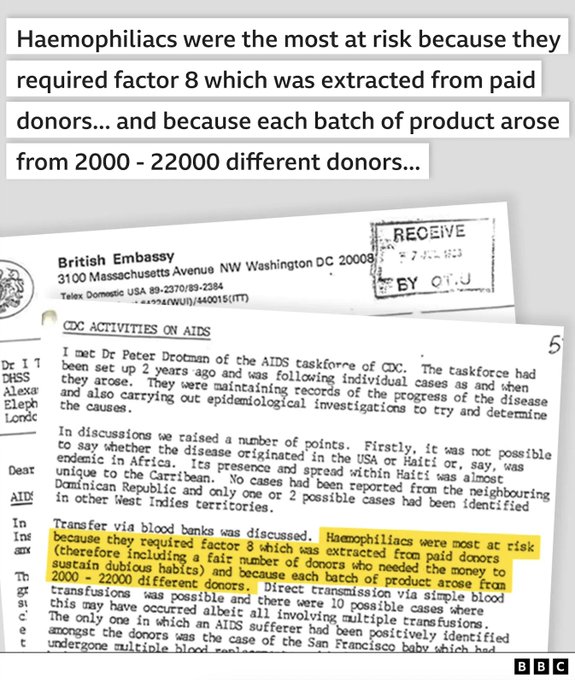

I reflected on this during the recent coverage of the NHS blood contamination scandal. Concerns were raised and communicated from UK embassy in Washington to the NHS, that Factor VIII supplies were derived from multiple donors who had been paid and who might have ‘dubious habits’ (referring, presumably, to intravenous drug use or even homosexuality). This intelligence was seen, but the most experienced people, the ones with decision making power and also the responsibility, decided that the real risk of shutting off the supply were greater than the theoretical risk of blood born virus infection. A great tragedy occurred.

In these examples, people did speak up, albeit ineffectively. Were they really whistleblowers? The writer of the memo from Washington, for example, fulfilled their duty in forwarding an opinion. But did they bang the drum and make trouble? Maybe not – they escalated to a certain extent.

Sometimes the question must be asked why did nobody speak up at all? Consider Volkswagen. It was not until two scientists ran real world emission tests around the city of Los Angeles that the emission of pollutants was shown to be up to 20 times higher then that stated by the manufacturer. Mark Besch and Hemanth Kappanna were members of the team. They are now famous for having revealed a great wrong. VW has paid out 33 billion in compensation. They did not blow the whistle, but they discovered the crime. The real question is, what about the engineers who facilitated this conspiracy over many years? How is it that something so clearly dubious did not stir them, did not make them go home and talk to their partners, did not induce them form a group, to represent their concerns and force the organisation to respond. How many wrongs are being done that are normalised, part of the culture, or so intrinsic to an organisation’s strategic priorities that to question it would be regarded as treachery?

I read about Volkswagen in Amy Edmondson’s book The Fearless Organisation. Here she talks about psychological safety, that is an environment in which team members feel able to speak up. This is not necessarily about things that are morally wrong, but about how things could be done better. Edmondson refers to several organisations where challenge is encouraged, for example Pixar and the fashion Eileen Fisher, where success can be attributed to early honest criticism.

▲

What makes a whistleblower? It is more than about being right. The unsatisfactory status quo will always be defended by the organisation that allowed it to develop. There will always be a reason why it exists. Unceasing demand, constrained finances, tradition, ‘that’s how it’s always been done’ – i.e. the bigger picture. As a single agent within a larger machine, the whistleblower may be accused of naivety, of not understanding the realities of the big bad world. Yet, they must be able to reach a conclusion that something must be done. This takes time. A lot of looking around, talking to people perhaps. Is this right? What do you think? I’m worried, are you? No – why not? Has it been normalised? Am I the only one who thinks this way? Is it me, or them? So much self-analysis and internal debate.

Then, the tussle between duty, personal morality and common sense vs the forces of inaction. Fear is the greatest – my job, my income, my comfort. Then self-doubt, based on your junior status perhaps. And scepticism, that nothing will be done anyway. You may have witnessed others talking about the same problem, for months or years… and if they did nothing, why should you? Or perhaps you will take your lead from role models. Your own moral orientation will be influenced by what they regard as right and wrong. How long will you be here anyway? If you are passing through, a specialty trainee for instance, what loyalty do you have to this organisation? You will be gone in six or 12 months. It will be somebody else’s problem. And then there is the exhaustion, the burnout. You may have had the energy and the drive to confront this issue once, but not anymore. It’s ground you down. You are five years from retirement. Better to lay low, involve yourself in uncontroversial activities. Do your job well, control what you can control.

Still, you decide to act. What are the characteristics that will make you win in the end. Medics like lists, mnemonics and artificial acronyms. Let’s use the P’s. You must be principled, you must be patient. You must recognise the process, where it applies, and use it. If you escalate, but have not gone through the usual routes, you will be criticised and asked to go back to square one. You must be prepared for your professional life to change, and perhaps your personal life too. You must be politically adept, even if it does not come naturally to you. You need people around you, like-minded colleagues to whom you can refer, and who can support you. As Peter Duffy said, don’t do this alone. Above all, you must be persistent. If you stop at the first hurdle, you will get nowhere. These are characteristics of effective people in any position. In the whistleblower, they are essential.

▲▲▲

* Re. Letby: there will be a public inquiry and the lessons will be drawn from that.

Available on Amazon (£0.79 on Kindle, $5.99 paperback)

Leave a comment